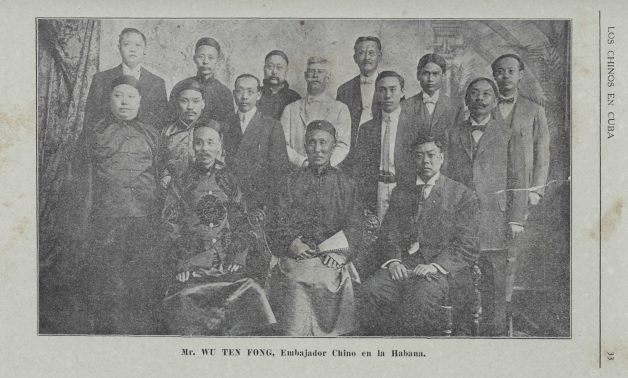

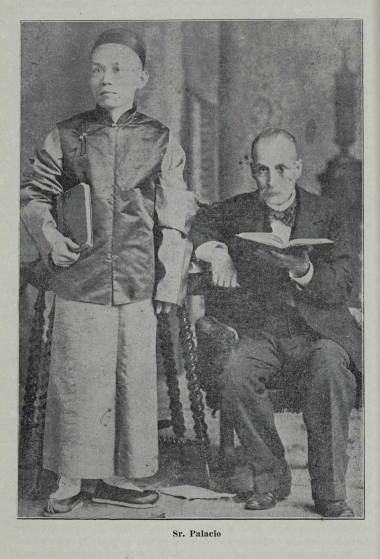

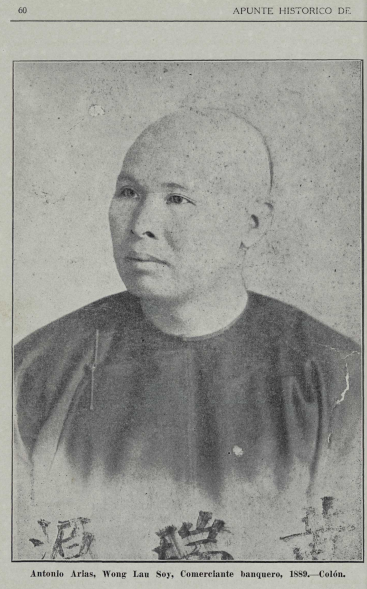

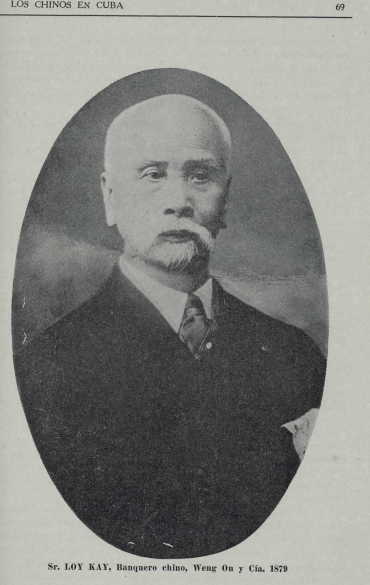

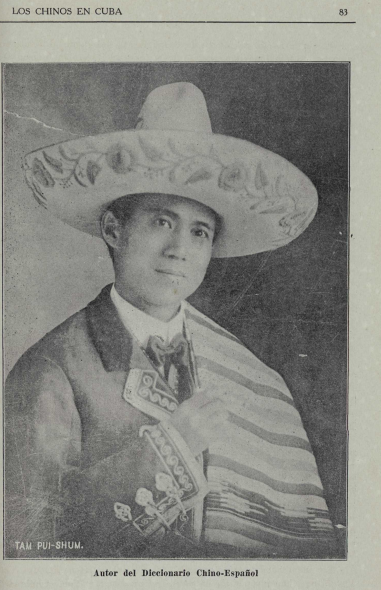

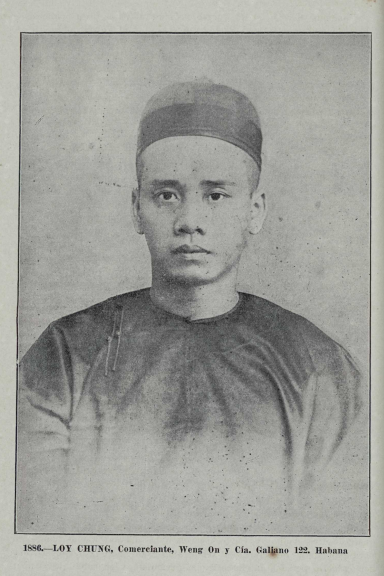

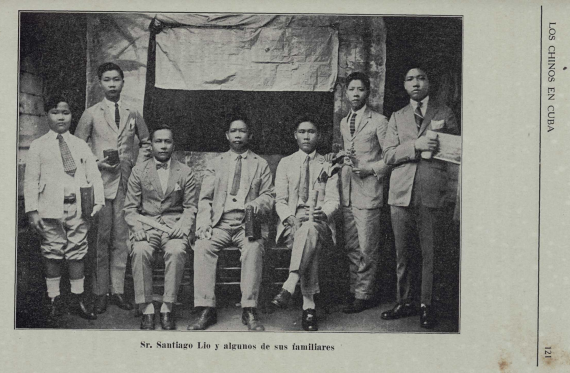

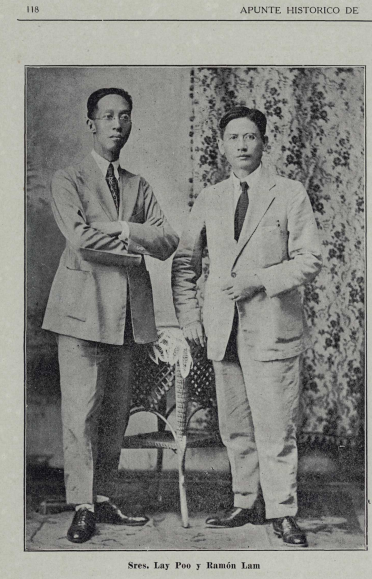

The author reads Latour’s text as helping answer the question What were the rich heterogeneities of color and class, social realities, and cultural hybridities that contribute to this lacuna of “transition” from a slave society to free society? (184). In tackling this question, the author points out how Latour is answering it in a similarly heterogenous manner, through a “hyperhybrid,” creating a dialogic narrative where each “written and visual form comprised a discourse of representation that connotes some sort of epistemic validity and form.” (191)

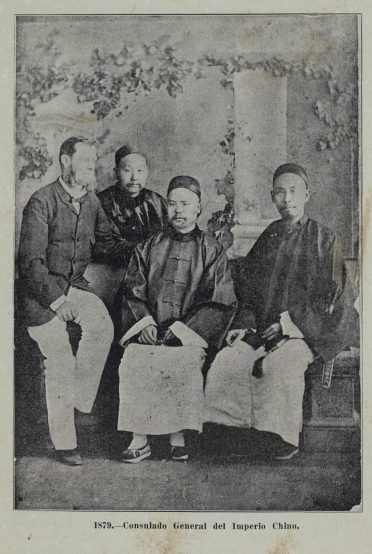

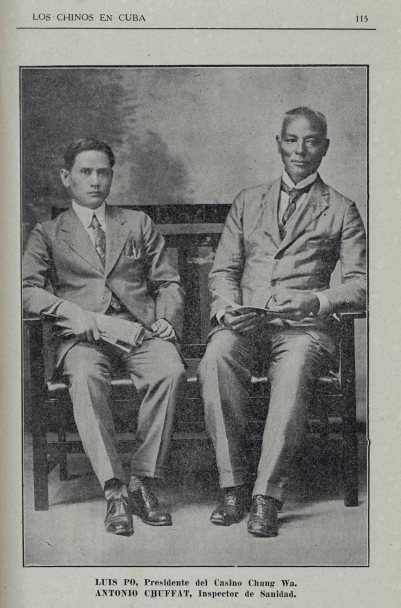

Such understanding of Latour can help open further the contradictions mentioned by Yun. If the text is understood in such a way, how is photography offering a way to think about the heterogeneities taking place during the transition to free society?How can the photographs provide insight into the class and gendered structure of the heterogeneity, even if the depiction of Chinese as a racial/ethnic category is in itself subversive? In other words, how exclusionary is the heterogeneity put forth by the photographs?

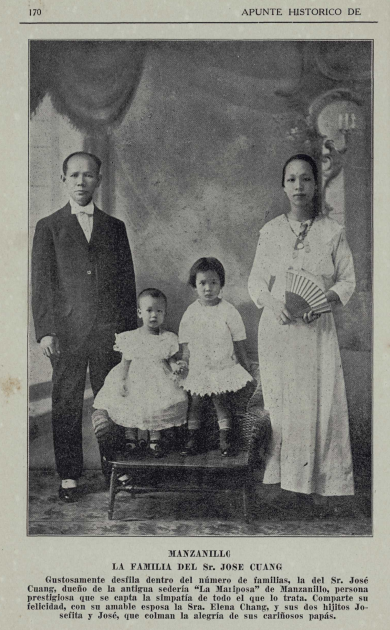

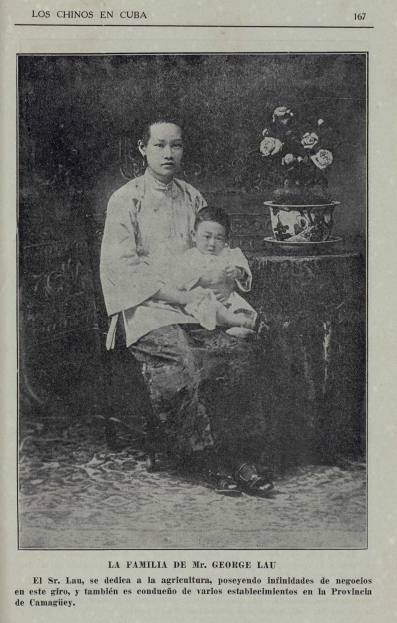

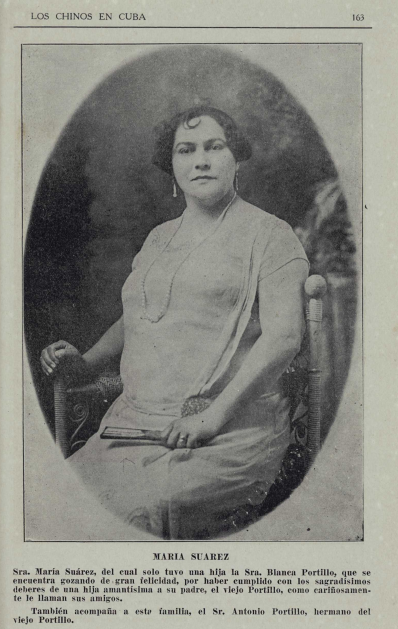

The contribution of photographic evidence to the heterogeneity of the text is most clear with the portraits of women. Yun points out that Latour barely mentions women in the main body of his work, relying on the photographs on the supplement in order to suggest “the importance of women in the building of a new merchant society and a free diasporic class…Their visual presence was indicative of their primary importance as symbols of class privilege, via the institution of heterosexual marriage, fa- milial lineage, children, and property” (227). I was wondering how Yun’s reading might be challenged with a close-reading of some of the photographs, or at the very least, through a quick glance of the photographs as a whole? What are the aesthetics of the pictures and the stylization of the people depicted? How is gender and class visibly organizing the visual aesthetics of the photographs?