If the question about diasporic identities is already challenging and problematic, the case of the Argentine artist, translator, editor and cultural agent of Japanese descendent Kazuya Sakai only adds more condiments. Sakai’s trajectory includes promoting Japanese culture in Argentina, occupying a pivotal role in the development of abstraction in Argentine painting, debating the meanings around Latin American art in México and being exhibited as an Argentine painter in New York. If a map always tells a lie -with its disproportionate scales, naturalized conventions and hidden power structures- but it’s through that lie that we organize our perceptions and understanding of a world and its processes, the same can be said, to some point, of labels and identities. The act of mapping, therefore, can be understood as the act of bringing up to front those questions.

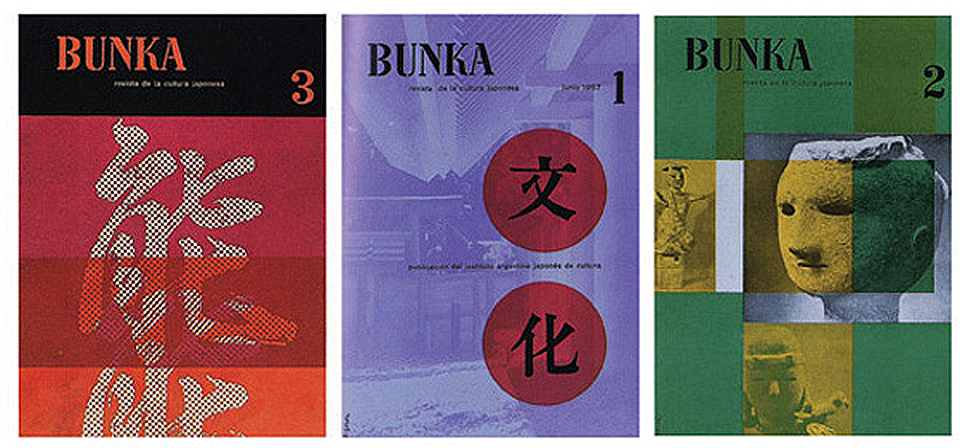

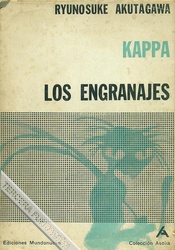

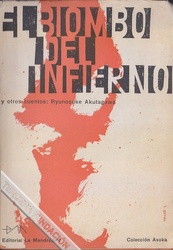

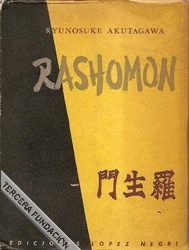

Kazuya Sakai was born in 1927 in Buenos Aires but at the age of seven he moved to Tokyo where he received his entire formal education, later graduating from Waseda University where he pursued studies in Literature and Philosophy. In 1951, without mastering the Spanish language, he decided to move back to Buenos Aires where he had a pioneer role in promoting Japanese culture. Among his activities as an agent for Japanese culture, in 1954 he curated the exhibition “Japanese stamps” at Bonino Gallery, founded the Argentine Institute of Japanese Culture in 1957 and one year later, the magazine Bunka which he also directed. As a translator, his work is of mayor importance for the dissemination of Japanese literature in the Hispanic world. As director of the Osaka collection at editorial Mandrágora (later known as Nuevomundo) he translated for the first time into Spanish works from Ryunosuke Akutagawa (El bombo del infierno y otros cuentos (1959); Rashomon y otros cuentos (1954); La nariz (1959); Kappa; Los engranajes, entre otros), Yukio Mishima (La mujer del abanico), among others.

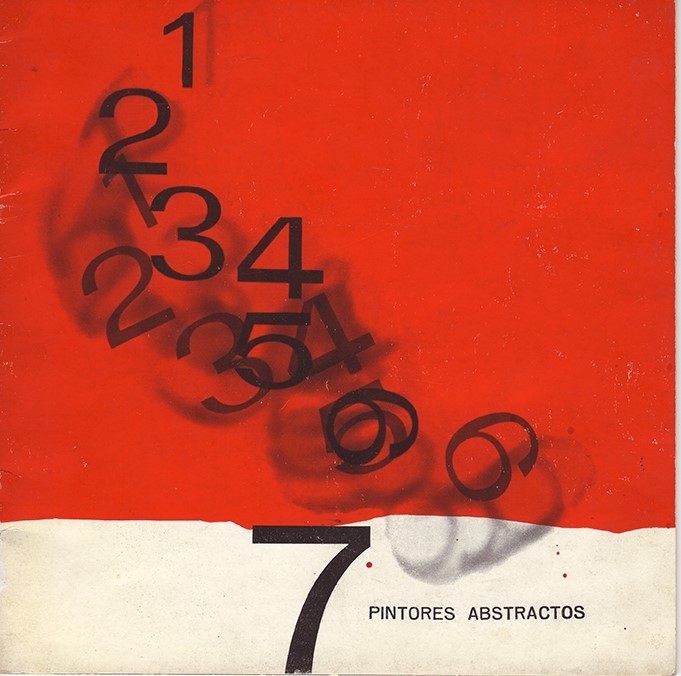

On the other hand, as a painter in Argentina, he participated in seminal exhibitions of Contemporary Argentine Art from the sixties, such as “7 pintores Abstractos” held at Galería Pizarro in the late 50s. Curated by Romero Brest and usually claimed of central importance for the Informalist Movement, the exhibit gathered works from Osvaldo Borda, Victor Chab, Rómulo Macció, Josefina Miguens, Martha Peluffo and Clorindo Testa. In 1960, he exhibited his work at Museo Nacional de Buenos Aires (under the direction of Romero Brest) along with the so-called “Grupo de los Cinco” (Kazuya Sakai, Sarah Grilo, José Antonio Fernández Muro, Clorindo Testa and Miguel Ocampo) which was defined by Marta Traba as the “most serious and responsible group in the argentine painting scene from that generation.” Meanwhile, as Sakai definitively turned into a renowned artist in the Argentine artistic field, nobody considered him or addressed him as Japanese, nor as an Argentine-Japanese artist.

In 1963 Sakai moved to New York, where he remained for three years before moving to México City. During his stay in the New York years of post-pictoric abstraction and pop art, his work made a radical shift towards geometrical abstraction and became close to jazz music, one of his major influences for his new productions. His displacement to New York, on the other hand, gives an insight of both the Argentine years where Internalization was fomented through a complex framework of institutions, curators, prizes and exhibitions and the American policies of fomenting Latin American Art as a political policy for creating an idea of Pan-Americanism, where art played a major role in spreading US influence along the continent in Post-Cuban revolution times. While the attraction for Paris did not diminish in the Argentine art scene, and Sakai’s contemporaries mostly made their way to Europe, a few of them settled in New York. In fact, Argentine painters that made the European choice also contributed to enlarge the importance of New York for the times to come since they discovered that in Paris “everybody just talked about New York.”

In 1964 Kazuya Sakai took part in the exhibition “Magnet: New York” at Bonino Gallery (originally from Buenos Aires, it opened its New York branch some years before) which reunited the work of Latin American -but mostly Argentine- painters living in New York.

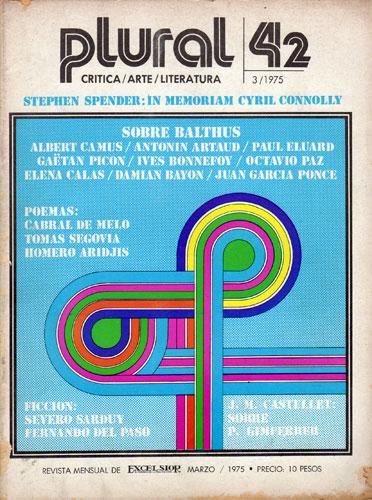

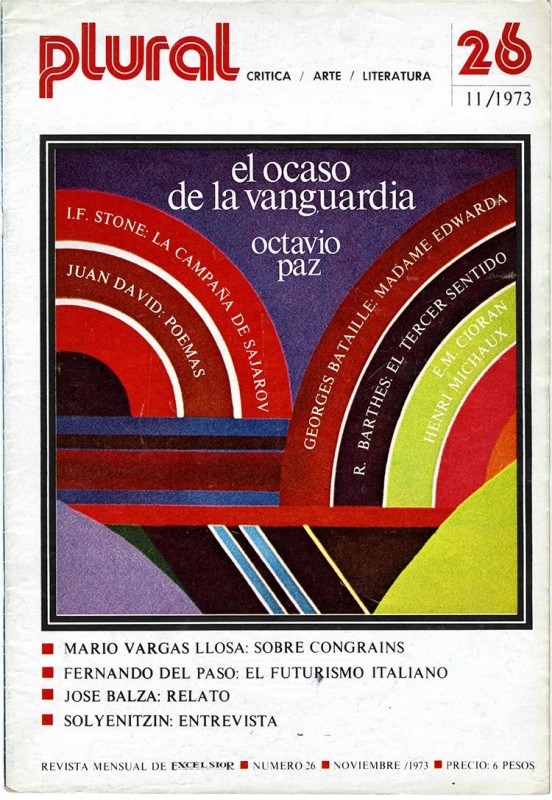

In 1966 Sakai moved to Mexico to hold a position as a professor in the new Center for Asian and African Studies at Universidad Autónoma de México. In this city, he joined the editorial committee of Plural magazine directed by Octavio Paz. Sakai joined the working group from the magazine since its beginning -the first number of Plural includes his translation into Spanish from El libro del ocio from Kenko- and works both as editor-in-chief for the visual arts section and illustrator. During his stay in México, Sakai continue to work as a translator and made the first translations of the works of Kobo Abe La perra (1971) y La mujer de arena (1972), the later published by Editorial Era). During his time at Plural he met Juan Acha, along with whom he organized the symposium “El artista latinoamericano y su identidad” (The Latin American artist and their identity”) held in Austin, Texas in collaboration with the University of Texas, the Blanton Museum and Damian Bayón who by that time taught classes on Latin American Modern Art. By organizing the symposium both Acha, Sakai and Bayón intended to animate the debate around art and literature in Latin America and promote an intellectual exchange around those topics between artists, critics, art historians and writers.

In México, Sakai’s paintings continued to be linked to geometrical abstraction, a style that he significantly contributed to spreading in México, but his Japanese references seemed to grow in importance as his series Homenaje a Korin and the Serie Genroku suggest. During his stay, he held two important solo exhibitions at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de México. In 1977 he exhibited Pinturas. Ondulaciones cromáticas y simultáneas, whose catalogues include texts from Acha and Bayón. According to Eder “If we could say that Mexican art at one stage exported social realism, Acha and Sakai wanted to turn the map of America upside down and make geometric abstraction flow from the South towards Mexico, without undermining the theorizing and dissemination of certain forms of conceptual art and performance.” His other major exhibition, Serie Genroku was held in 1987 and it was inspired in the Japanese XVII Century.