In her book Unsettled Visions, Professor Margo Machida opens with the question: how do artists of Asian heritage, whether foreign or U.S. born, conceptualize the world and position themselves as cultural and historical subjects through the symbolic languages and media of visual art? In the first chapter, Machida maps out multiple thematics available for considering the circulating discourses on Asian/American visual culture and the role these discourses play in conceptualizing formations of identity, community, and globalization. The thematics she considers, such as iconographies of presence, the diasporic imaginary, and collective memory, all fall under an umbrella framework she calls positionality. Positionality, she explains, is a framework for considering the spectrum of social critiques that point to the situatedness of our knowledge of and actions in the world. In the context of Asian American artwork, positionality welcomes coexisting modes of Asian/American subjectivity as well as conflicting, mutable narratives.

She also introduces the three sites that have constituted Asian American Art: identity politics and community arts movements in the context of U.S. multiculturalism, the tension between globalization and localism in the U.S. art world, and critical theory focused on articulations of difference. In the chapters that follow, Machida brings in the work of many different Asian American artists that grapple with the very notion of an “Asian American” identity. These artists engage with different thematic subjects such as diaspora, globalization, or hybridization. Whereas Yong Soon Min’s installation “DMX XING” functions an space for viewers to engage with acts of reconstruction and interpretation when encountering the histories of postwar experiences of Southeast Asian refugees, the work of Ming Fay is more concerned with the metaphysical connection with man and nature evident in moments of contact, reconfiguration, and “cross-cultural pollination.” Bringing together artists so apparently different from one another, Machida illuminates “the cross-cultural connections and slippages that emerge as artists of non-Western ancestry and the West dynamically produce, permute, and retransmit images of one another in an elaborate, frequently ambiguous and paradoxical process of mutual transformation” (Machida, 269). The purpose of identifying artists as “Asian/Americans” is not to reify Western conceptions of race, geopolitics, and otherness, but to expand on a large body of collective knowledge that requires viewers to “engage in strategic acts of translation and ongoing dialogue.”

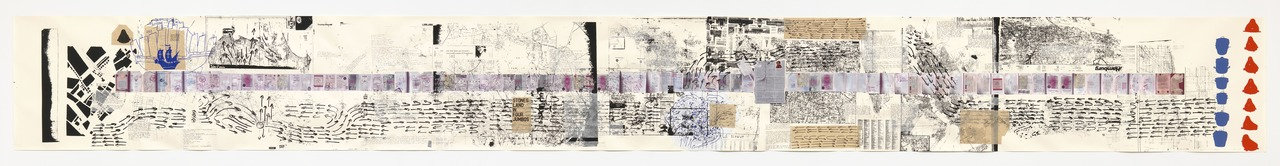

Machida highlights the way global migration in the late modern period has disrupted the traveler/native dichotomy. Experiences of forced or voluntary migration both to and within the United States always involves a spaciotemporal negotiation of one’s past and present surroundings. This made me think of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s piece Untitled 2008-2011 (the map of the land of feeling) which serves as an artistic record and reflection of his travels. Tiravanija is a Thai artist born in Argentina to a diplomat, and grew up in Bangkok, Ethiopia, and Canada. He now splits his time between New York, Berlin, and Chiang Mai, Thailand. The scrolls in Untitled 2008–2011 (land of the map of feeling) I-III incorporates his passports, visas, and stamps, overlaid with city plans and time zone lines printed using multiple techniques. Other images on the scrolls allude to artists that have influenced or inspired him. To me, his project embodies the multiplicity and collectivity inherent in narratives of migration that Machida wants to emphasize in Unsettled Visions. In what way does such an alternative imagining of movement and migration force us to think outside strict lines of national borders, time, and identity?

Unsettled Visions asks readers to reconsider the way they receive and respond to representation of multiculturalism in the art world. Machida recalls in chapter one bell hooks’ recognition that there is always something more primary at play when assertions of difference do not reflect the interests of the majority, and they are met with indifference, resentment, resistance, or rejection. There is a productive tension in the way art which engages with themes of racial difference and the history of global migration is often met with wariness or even hostility. It is not enough for the United States to welcome immigrants or celebrate itself as a nation defined by multiculturalism proven by the presence of “others” alone. The artwork produced by Asian or Asian American artists must be recognized as an expression of a positive/generative lack or failure to fit in neatly with the mainstream teleology of Western dominance and the popularized discourse of historical truth and national belonging.