During the semester, a big question that came up was the definition of Asian American identity. What is it to be Asian American and, thus, what can be considered Asian American art? Though my research did not focus on answering these questions, the life and art of the Japanese-Brazilian artist Tomie Ohtake opened my eyes to how to understand diasporic identities and art.

In December 2014, the filmmaker Tizuka Yamasaki premiered the documentary Tomie, which offers a delicate and affectionate portrayal of the artist’s universe. Intimate glimpses into Tomie’s life are intercut with interviews carried out with three art critics Paulo Herkenhoff, Agnaldo Farias and Miguel Chaia. Aged 100 to 101, Tomie painted around 30 new canvases, and kept working up until her death in February 2015. The documentary presents Herkenhoff, Farias and Chaia’s view that Ohtake’s art represented a very interesting bond between two cultures: between the “oriente” (eastern civilization) and the “ocidente” (western civilization). According to them, she developed a unique path and language, creating her own world of art: “Existe um país chamado Tomie. Ela inventou um território.” (There is a country named Tomie. She invented her own territory), one of the critics concludes.

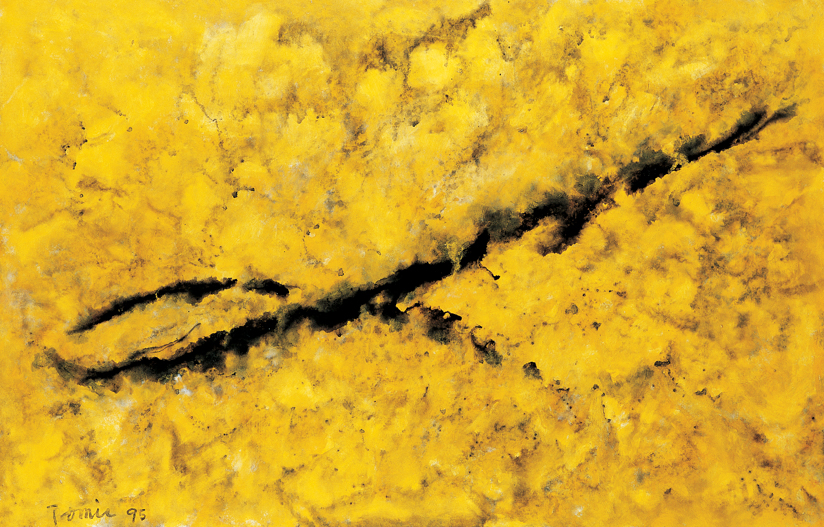

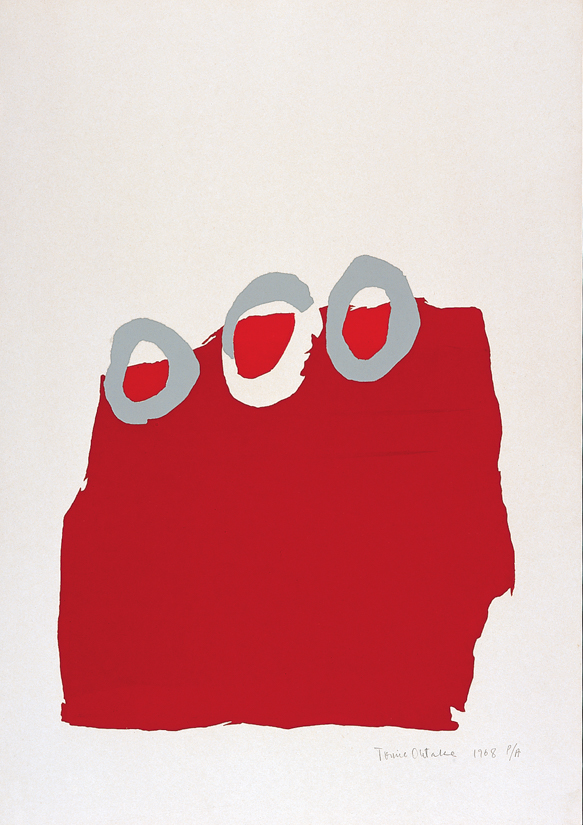

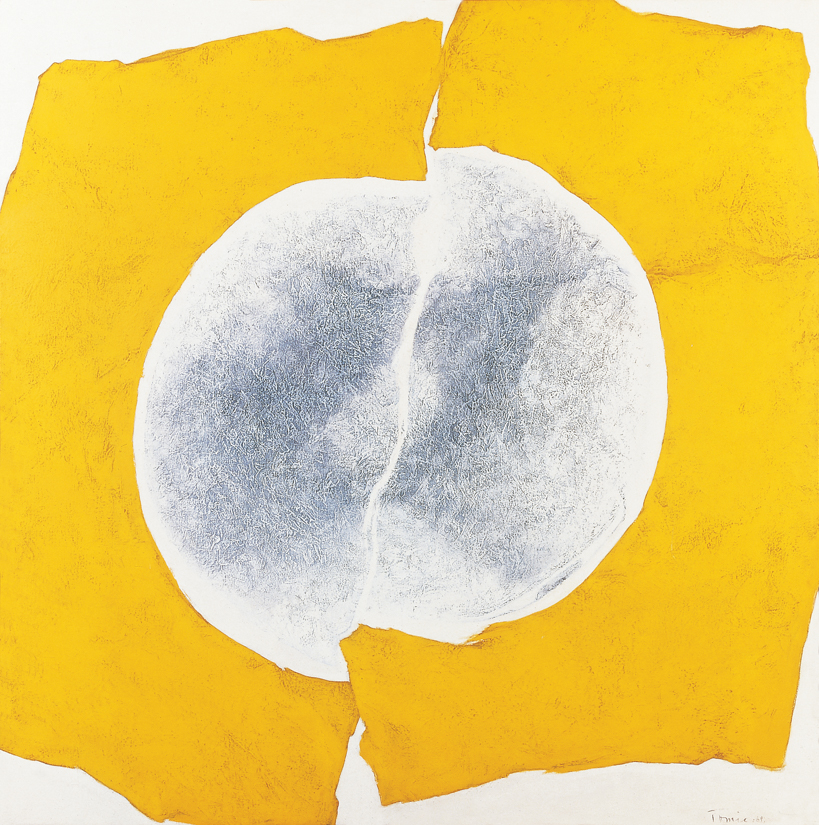

Tomie Ohtake used the typical “pintura Brasileira” (Brazilian painting style). The geometric content of the art is marked by the hand’s vibration and imperfection. Ohtake used to say that as she used her hands, her forms were a little bit wrong, but it was in those little mistakes that the strength of her art emerged. Her forms involved disparate elements, from the biological nature of the ocean to cosmic events of nature.

Yet, Ohtake would claim that such results would only be created after she was done, never having in mind the final piece of art. During her interview she stated: “fazer é o que gera o resultado” (Doing is that which created the result). Her geometry, according to the art critics, was intuitive. The forms emerging in her art started from a goal provoked by the desire to fulfill an empty space. Close readings of Tomie’s art suggest that many of her forms look like packages of sweets and fruits from her native city Kyoto, Japan. Of course, she never would think about this in order to develop her paintings. As these forms remained in her subconscious, they naturally flourished in her geometry.

For Tomie, form is what defines her art. In the same way, form is what also defined a person. With a heavy Japanese accent, she stated during the interview:“Forma é a formação da pessoa. Primeiro tem qui definir como colocar na tela.” (Form is what makes a person. First, we have to define how to put it on the canvas.) According to the narrator, the forms in Tomie’s art are, on one hand, marked by her Japanese heritage, having graphic elements from Japan, and, on the other hand, they are never explicitly conveyed in the final piece. Thus, the narrator argues that this relationship is what makes her art so unique and powerful, showing the connection between two different cultures.

Tomie Ohtake passed away in February 2015, having lived to 101 years of age. During her last year of life, she painted about 30 paintings. Although she is no longer alive, her art still is displayed in 35 public places around Brazil and Japan. During her career, Tomie Ohtake aimed to share her work not only with people who would go to her exhibitions but with everybody. She wanted to be able to talk with everybody through the language of her art. Interestingly, her favorite colors, which she often used in her paintings and public works were yellow and red. Yellow was the first word she chose to describe Brazil when she first arrived in São Paulo in 1936 to visit her brother. For Tomie, everything she loved in Brazil (the sun, the streets, the foods, etc.) reminded her of the color yellow. Although she does not explain the reason for the red being another of her favorites colors, one can easily associate red with her favorite form, the circle, and connect with the Japanese flag featuring a red circle over a white background. In fact, white is her third favorite color, and it was the color that dominated her last art exhibition before she passed.

![Ohtake’s public work Estrela do Mar [starfish], made from metal and designed for installation at Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, in Rio de Janeiro. The work was dismantled in the 1990s and eventually lost.](https://madap.tome.press/wp-content/uploads/sites/242/2017/04/tomie1985lagoafreitas.jpg)

Mapping

Why Digital Media? Digital media is a way to help my audience to have a much better experience and facilitates their engagement and full understanding of the content. For example, during the first phase of my research about Tomie Ohtake, which involved mostly collecting data and learning about the artist, I did not know how my final project would evolve. Nor did I expect to create a map from what I was learning. After thorough research, my biggest challenge was that I fell in love with Tomie. For me, it was crucial that my audience also learned about her life story. It was not only Tomie’s art that I want to talk about, but also her personality, the most intimate ideas behind her art, and most importantly, the impact she had in the world. How can I convey all I learned about Tomie’s fascinating 101 years life without writing a book or making this presentation exceed fifteen minutes? Well, this is how: Digital Media!

By using the Timemap (above) I was able to introduce Tomie’s life story with details, and show her art development throughout her career showing each place she had an influence globally. This was especially important for diasporic art because the audience is able to visualize each place that Tomie’s art had a presence, highlighting the combination of two cultures, Japan and Brazil, with examples of pieces of art. Thus, the timemap allowed my audience to effectively visualize several types of information at the same time and, indeed, have a much more enjoyable experience.

Yet, this was not enough to demonstrate Tomie’s legacy and why she should be considered a remarkable artist. I realized only after full collection of data that Tomie not only participated in 20 art salons abroad, over 120 individual exhibitions, and almost 400 group exhibitions all over the world. Most of them included important political messages such as protest against dictatorship and women’s presence in art. As you can see on the map above, one can easily visualize the extent to which Tomie’s art had an impact in the world. The red dots show her group and solo exhibitions designed to convey specific messages to the public. For example, in 1973 Tomie participated in an exhibition in Tokyo and Kyoto called Japanese Artists in America, illustrating the presence of diasporic art. In 1982, she had another exhibition in New York about women artists in the Americas. Thus, I was able to portray her voice and presence globally on this map which I made using Carto software.

In addition, Tomie’s numerous public art installations are still “talking” to Brazilians and Japanese even after her death. Since they are public works and deserving of greater attention, I further illustrated them in the header of this page. The map allows my audience to click on each public work so they can see the art information and the exact location.

Although my digital experience allowed me to present Tomie’s story in a very innovative and effective manner, it is important to keep in mind that maps can also give a distorted image of reality. For example, the map showing the locations of Tomie’s exhibitions highlights the influence the artist had globally. However, her art was almost exclusively produced in Brazil, mainly in São Paulo. Thus, one could conclude that the world’s influence on her work is much smaller than the impact Tomie Ohtake has had in the world. This observation is not designed to diminish Ohtake’s influential power. Indeed, Tomie’s art is known all over the world. Rather, this critical observation serves as a reminder to always be aware of optical illusions that maps may contain. It is important to remember, for instance, that our standard cylindrical map projection known as Mercator Projection distorts landmass sizes, making the poles look much bigger than the equatorial territories. In Tomie’s map, we also have to keep in mind that Tomie’s influential impact is being limited by the ability to find historical data as well as by optical distortions. To conclude, mapping in humanities can be a great resource for enhancing our studies in a specific subject as long as we consider the “lies” that all maps inherently tell.

Yamasaki, Tizuka. 2014. Tomie. Brazil: Scena Filmes, Instituto Tomie Ohtake "Bibliography." Accessed 27 Apr 2017. http://www.institutotomieohtake.org.br/en/.