Margo Machida’s Unsettled Visions offers a comprehensive and nuanced look at the plural, changing meanings of the “Asian-American artist” category, its social and political role, and the overlaps and differences in the themes these artists tackle. To be an Asian American artist is more than to be Asian and American and an artist, or to make art that utilizes Asian symbols or practices. Machida points to the ways that this label should be understood not as a simple, restricted identification based on race or provenance of birth, but rather as an indicator of a particular mode of engagement that is relational, contextual and highly “situated” (45). In other words, the category of Asian American, and art produced by those within this category, takes meaning in context. Macroscale historical context, microscale personal history, and the even physical space effect the meaning of a visual representation, and inform the artist who is creating these visuals.

What interested me about this argument is that it points to not simply to the constantly-evolving nature of an identity marker like Asian American, but also the constantly evolving meanings one may be able to draw from images. If context and position inform how an artist represents the world, then so too will these inform how viewers respond. An image with one meaning in a particular moment can easily acquire a new one in a different moment. Machida even explores this phenomenon of changing understandings of representations by charting the fluctuations in how artists’ responded to the label of “Asian American artist.” Just as geography is an epistemic category (194), so too is time. Time is not simply one of many variables we can catalogue, but also the larger space itself in which all our other variables take on meaning.

For us who are attempting to create both meaningful and informative visuals, this conclusion raises several interesting questions. How symbolic and abstract should our representations be? Should we attempt to fix the meaning we are attempting to communicate as firmly as possible? Or, is it desirable to permit and acknowledge meaning to change? If we try to fix meaning, should we do this through the image itself, or through our accompanying words? What if we leave the image open, but then explain our choices thoroughly in our texts?

On the one hand, utilizing a more artistic, interpretive perspective may allow us to create images with which a viewer connects on a more profound level. Perhaps, also, in leaving meaning open, we engage in a more intellectually honest type of visualization that points to fact that the data we collect is interpreted; it is not some tangible Truth spontaneously emerging from the world. On the other hand, we do then open the door for the meaning of our images changing drastically with the times. Perhaps, then, what we create will take on entirely unintended or unintelligible meanings that compromise the informative aspect of our projects.

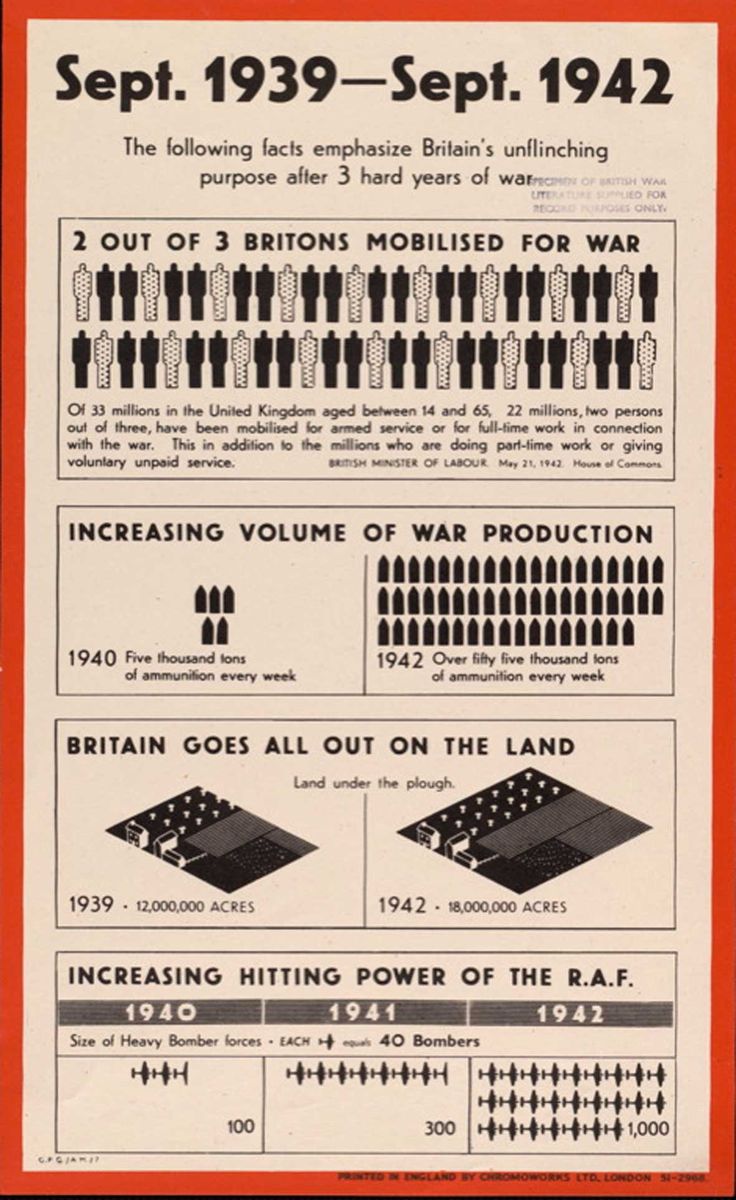

Statistics-heavy propaganda posters like the one below are a great example of how the meaning of an image can change. At the time, I would assume most residents of Britain might see this as a purely informative image. We, however, see the choices of symbols, colors and data as all designed to elicit participation and cooperation from British citizens. The persuasive, peer-pressuring qualities of this image come to the forefront for us.

A link to the artist profile of Titus Kaphar, whose work reconfigures famous historical paintings to comment on marginalization:

https://www.jackshainman.com/artists/titus-kaphar/

The article below provides and interesting summary of changing word meanings over time: