A Geography of Movement: Indian Indenture in the Caribbean

In the 1830s, after the abolition of slavery, the Indian indenture system provided cheap labour to the British sugar plantation owners in the Caribbean. Workers from India were recruited for “voluntary” labour in Guyana (then British Guiana), Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Surinam, and Mauritius, among others. The system officially ended in 1917, a century ago, but its enduring legacy can be traced in the large Indian diaspora in the Caribbean, and in the stories that emerge from the descendants of indentured workers trying to find a home in their family narrative of migration.

Beyond bare numbers, however, there exist contemporary narratives of indenture that seek to understand the reality of this system that has been called a new form of slavery. Due to the lack of actual stories from workers of indenture, their descendants, attempting to understand the experience, resort to works of imagination in order to represent indenture. Arjun Appadurai, in his work Modernity at Large, writes that mass migration, through the creation of diasporic public spheres or public spheres that transcend geographical and political boundaries, seems to compel the work of the imagination. He writes, “the work of the imagination […] is neither purely emancipatory nor entirely disciplined but is a space of contestation in which individuals and groups seek to annex the global into their own practices of the modern” (Appadurai 4). For him, and for the descendants of indentured workers, these works of imagination become collective social facts.

Andil Gosine belongs to this relatively small Indo-Caribbean community that claims a heritage in indenture. He describes himself as a professor and as a descendant of indentured workers, but not much else. The lack of a personal history perhaps speaks to a rejection of that specific form of identity building. His work, which is in focus, thus is an interrogation of what identity means in such a fractured history of movement and migration. In his text titled Visual Art after Indenture: Authoethnographic Reflections, he explores three of his own exhibitions to reveal the intersection of the personal (autho-) and the communal (-ethnographic) as foundational to his work.

Wardrobes

This exhibition can be seen as exemplary of how, for artists seeking to represent indenture, the personal and the socio-historical are always inextricably linked. For Gosine, a personal heartbreak set him on the way to imagining indenture in an effort to understand a history “that preceded [his] existence, but which remains formative of it” (Gosine 105). The exhibition consists of four objects: a cutlass shaped brooch, a rum and roti bag, doctor’s scrubs with an image of Gosine’s parents, and a headscarf with an anchor tattoo like the one his grandmother had.

Both “Rum and Roti” and “Made in Love” present objects that provide for a nostalgic moment for the audience who knows of stories of indenture that involve things like sugarcane, a search for a perfect roti, and old studio pictures with the artificial background of European attractions. Gosine acknowledges that “Most of the audience were descendants of Indian indentured workers, so there was a very specific way in which they connected to the backdrop” (Gosine 106).

“Cutlass” and “Ohrni” both have gendered aspects to them. Gosine’s grandmother is the inspiration behind both and both have multiple dimensions to them. The cutlass, used in the sugar plantations to cut sugarcane and used as a weapon for protection; the headscarf, a sign of modesty reappropriated by women to assert femininity (“to feel beautiful”). In Gosine’s words, they are “as much markers of oppression as they are evidence of the creative agency of women who lived through miserable conditions of colonisation” (Gosine 2). Thus, for artists like Gosine, these specific experiences of indenture are part of a past they are not intimately familiar with; however, to have them represented as personal objects through which indenture can be viewed becomes a way to invoke the personal in confrontation with the communal history.

Our Holy Waters, and Mine

Gosine’s history, and that of indenture, is one characterised by or inextricable from movement. It complicates the idea of “roots,” so intrinsic to discourses on identity. In a state of constant movement, where no one place is a home or a base you can go back to, Gosine’s art seems to ask – what is it that lasts? Is it objects, as seen in Wardrobes; is it people; or perhaps, is it memory – tenuous, imperfect memory?

This visualisation shows, simultaneously, the journey from Calcutta to the Caribbean of the indentured workers and Gosine’s personal movement from Trinidad to North America to Europe. It brings together a personal and a historical journey but, more important, it shows the back and forth of Gosine’s own movement, along with an inability to go “back” to either of the places that might be considered a “home” – India or Trinidad.

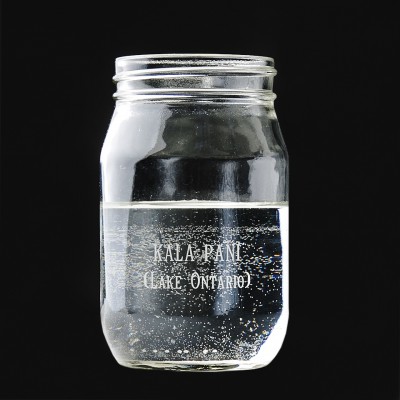

Gosine’s second artwork titled “Our Holy Waters, and Mine” draws heavily from Mauritian poet Khal Torabully’s idea of “Coolitude,” which finds a shared heritage in the experience of the journey taken together by the indentured workers. “Coolitude” is an identity of movement – it explicitly denies the point of origin as the basis for identity and relocates it in the journey or in the movement. For this art work, the Ganges becomes representative of India and its rejection as holy becomes a rejection of India as a “home” or a basis for identity for those like Gosine who migrated. Instead, their holy waters become the kala pani (black waters) that they crossed together. Gosine brings out 12 jars, each etched with the name of a waterway that has been involved in this history of movement – six crossed by the indentured workers (Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Paria, Berbice River) and six that Gosine himself has crossed in his life (La Seine, The Thames, Rio Manzanares, Lake Ontario, Potomac River, Hudson River). “Holy” waters in their own right, none of these are the Ganges however. In this way, “Coolitude” and Gosine’s aesthetic practice interrogates the difference a “real” history (India) and an “actual” history and, as Gosine writes, “refuses the reduction of the Indo-Caribbean experience to an Indian root, whether biological or geographic” (Gosine 111).

Gosine’s art provides a way of interrogating the geography of indenture and that of “coolie.” Not simply contained in the journey from Calcutta to the Caribbean, it extends into the personal and everyday, and is also shaped by the imaginative acts of artists like Gosine. In this final map, I trace the origin and evolving use of the word coolie across space and time. Not intended to be comprehensive or thorough, the map seeks to demonstrate the global scale of this identity that is so rooted in movement and migration.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. Print.Gosine, Andil. "Ohrni and Cutlass." Caribbean Review of Gender Studies 6. 2012. 1-3. Print.Gosine, Andil. "Visual Art after Indenture: Authoethnographic Reflections." South Asian Studies 33. no. 1: 2017. 105-112. Print.